The Effectiveness of Psychedelics to Treat PTSD

Author: Teyline McLean

Neuroscience In Review

Introduction

What is PTSD?

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) can develop after experiencing or witnessing a dangerous or life-threatening event (National Institute, 2019). Most people think of military veterans having PTSD, but it can also come from car accidents, sexual assault, and abuse (Miao, 2018), (Schrader, 2021). Based on the current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-5 (DSM-5) diagnostic criteria for PTSD, one must have symptoms from several key categories: intrusion, avoidance, negative changes in mood, and changes in reactivity. Symptoms can include flashbacks, avoidance of triggers, dissociation, irritability, difficulty sleeping, etc. (Schrader, 2021). PTSD is often comorbid with other disorders such as anxiety, depression, and substance abuse, with 80% of patients with PTSD having at least one other diagnosed disorder (Miao, 2018). The mechanisms behind PTSD are not fully known, although it appears the neuroendocrine and immune systems are involved. The activation of stress response pathways such as the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and sympathetic nervous system play a role in the development of PTSD (Miao, 2018). People with PTSD have elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-a), interleukin-1beta (IL-1b), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) (Passos, 2015). There is also a genetic component to PTSD with an estimated 30% heritability (Miao, 2018).

Paroxetine and sertraline, both selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), are the only two FDA approved medications for PTSD and it is estimated that 40-60% of patients do not respond to these drugs (American Psychological, 2017), (Krediet, 2020), (Mitchel, 2021). Psychotherapy is considered the first line of treatment and focuses on cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), cognitive processing therapy (CPT), and prolonged exposure (PE) therapy (Watkins, 2018). While these therapies do help many reduce their PTSD symptoms, they can be emotionally challenging, and have an average dropout rate of 18%, meaning that not everyone experiences a benefit (Watkins, 2018). PTSD is a serious and chronic problem for many, and a more effective treatment is needed, leading people to look at psychedelics as a potential treatment.

What are Psychedelics?

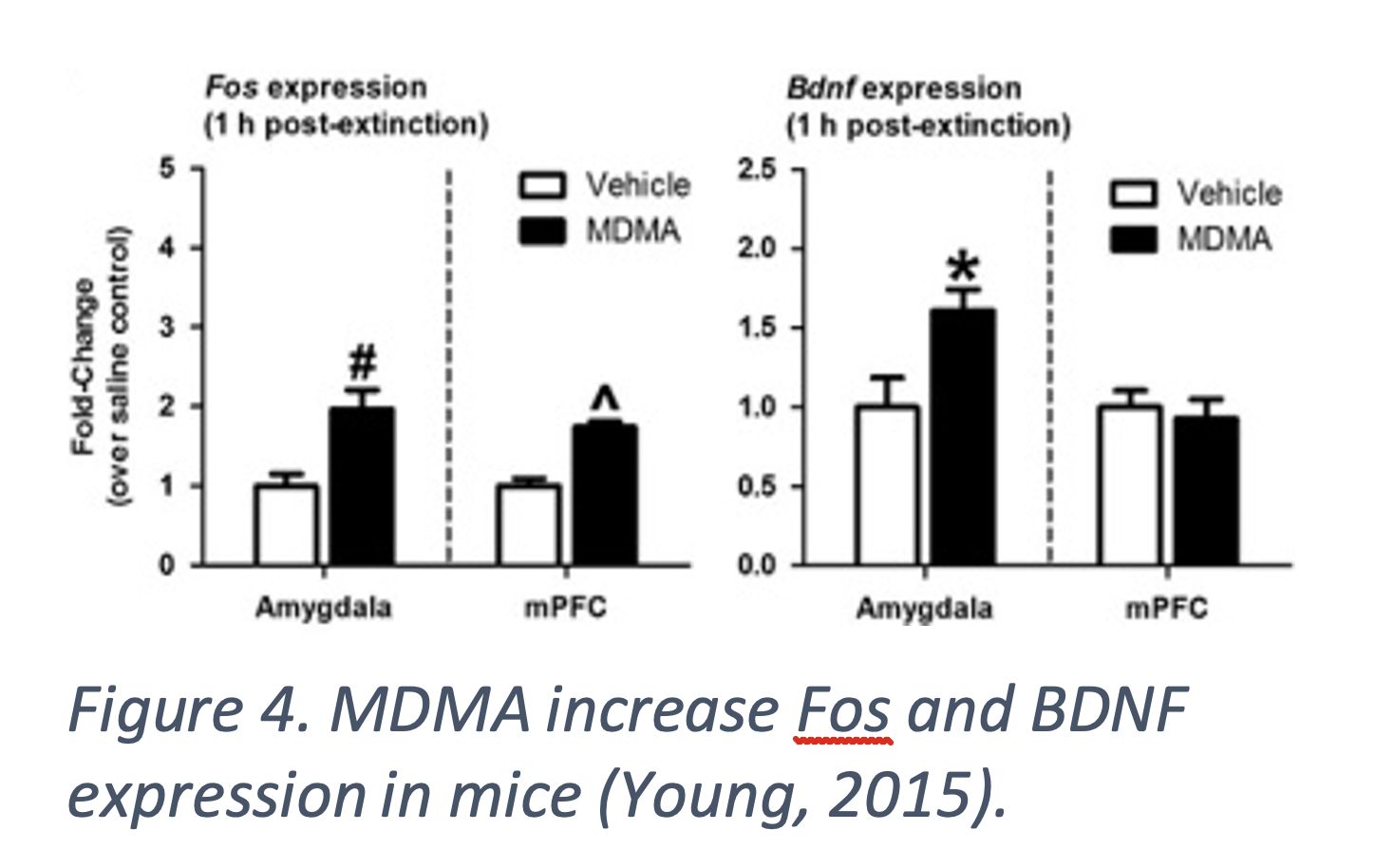

Psychedelic drugs include psilocybin, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), ketamine, and cannabinoids, among others. They produce an experience of altered consciousness, and symptoms can include hallucinations, and changes in mood, sensory perception, and perception of the self and the environment (Krediet, 2020). Most psychedelics, especially the classic psychedelics like psilocybin and LSD, act as serotonin receptor agonists with a high affinity for the 5-HT2A receptor, although some also interact with other receptors. When a 5-HT2A receptor antagonist is administered, it blocks psilocybin’s effects in the brain (Vollenweider, 2010). The activation of 5-HT2A receptors leads to an increase in glutamatergic activity in pyramidal neurons in layer V of the prefrontal cortex (PFC) (Vollenweider, 2010). MDMA is an entactogen, and produces unique symptoms of increased empathy, prosocial behavior, ability to tolerate distressing memories, and reward for pleasant memories (Feduccia, 2019), (Sessa, 2019). MDMA acts as both a serotonin and norepinephrine agonist (Sessa, 2019). It also facilitates the release of oxytocin, a hormone associated with social bonding, and can affect levels of brain derived neurotropic factor (BDNF) in the amygdala, thought to mediate MDMA’s therapeutic uses for PTSD (Young, 2015), (Sessa, 2019). Ketamine and phencyclidine (PCP) are dissociative anesthetics and block glutamate N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors. This increases the glutamate levels in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), thus increasing the neuron’s activity. The excess glutamate acts on GABAergic neurons, reducing activity inhibition, and this is thought to cause the psychotropic effects (Quirk, 2009), (Vollenweider, 2010). Interest in psychedelic drugs’ therapeutic uses is increasing and the FDA has recently granted psilocybin and MDMA assisted psychotherapy a breakthrough designation to treat depression and PTSD respectively. Preliminary research shows they can be effective for treating conditions like depression, anxiety, and pain (Krediet, 2020).

This literature review aims to determine whether psychedelic drugs can be used to treat PTSD. MDMA and ketamine assisted psychotherapies specifically will be examined for PTSD treatment efficacy and safety. Psilocybin and cannabinoids will be examined for future research.

Psychedelic Drugs’ Treatment Potential for PTSD

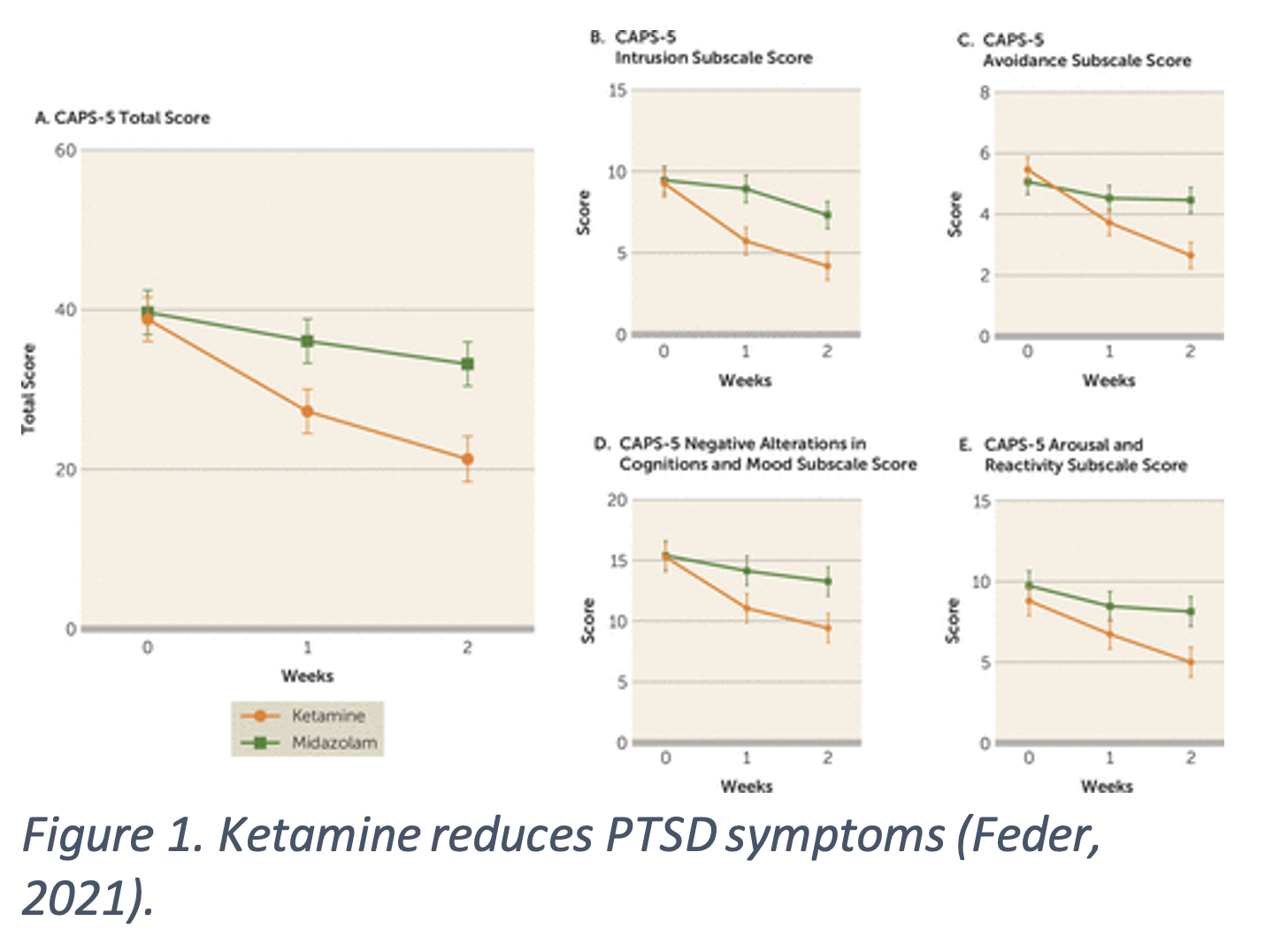

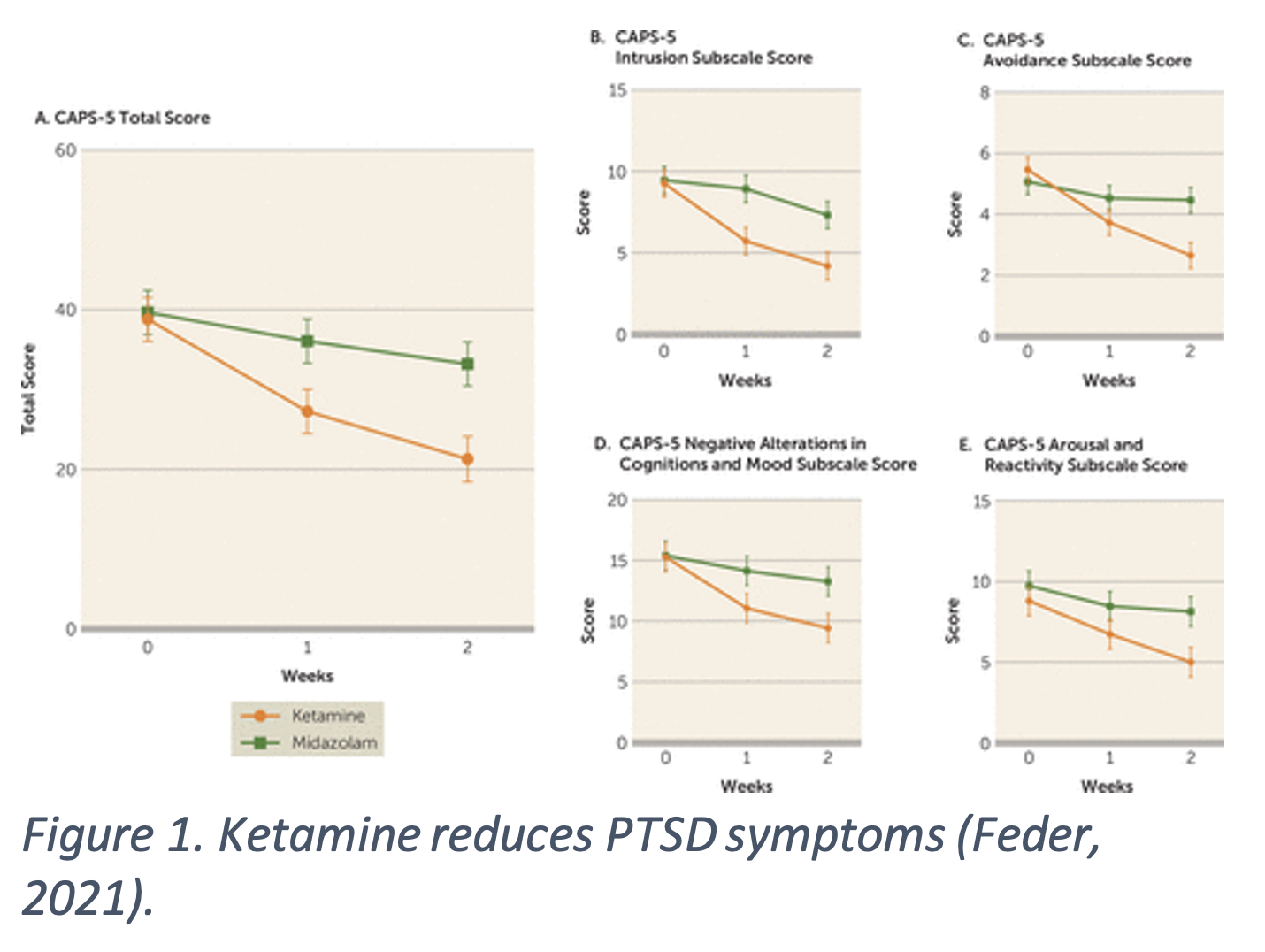

A single infusion of 0.5 mg/kg ketamine reduces PTSD symptoms compared to midazolam, a benz4odiazepine acting as an active placebo. PTSD symptoms were reduced within 24 hours of administration and stayed low at a two-week follow up (Feder, 2014). Repeated ketamine infusions also reduced PTSD symptoms when compared to midazolam. The ketamine group had significantly improved total and subscale scores on the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5), a common test of PTSD symptoms (Figure 1.). Symptom improvement was sustained for an average of 27.5 days after, much longer $4the placebo group, 67% versus 20% (Feder, 2021). PTSD is often comorbid with major depressive disorder (MDD), making both disorders harder to treat. Patients with cooccurring PTSD and MDD received six ketamine infusions and symptoms improved for both disorders. PTSD symptoms had a relapse time of 41 days and depression symptoms had a relapse time of 20 days (Albott, 2018). Repeatedly administered at subanesthetic doses, ketamine seems to be effective at reducing PTSD symptoms and comorbid MDD symptoms.

A single infusion of 0.5 mg/kg ketamine reduces PTSD symptoms compared to midazolam, a benz4odiazepine acting as an active placebo. PTSD symptoms were reduced within 24 hours of administration and stayed low at a two-week follow up (Feder, 2014). Repeated ketamine infusions also reduced PTSD symptoms when compared to midazolam. The ketamine group had significantly improved total and subscale scores on the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5), a common test of PTSD symptoms (Figure 1.). Symptom improvement was sustained for an average of 27.5 days after, much longer $4the placebo group, 67% versus 20% (Feder, 2021). PTSD is often comorbid with major depressive disorder (MDD), making both disorders harder to treat. Patients with cooccurring PTSD and MDD received six ketamine infusions and symptoms improved for both disorders. PTSD symptoms had a relapse time of 41 days and depression symptoms had a relapse time of 20 days (Albott, 2018). Repeatedly administered at subanesthetic doses, ketamine seems to be effective at reducing PTSD symptoms and comorbid MDD symptoms.

MDMA

In an 18-week trial, 3 sessions of MDMA, at 80-180 mg doses, alongside psychotherapy significantly reduced PTSD symptoms based on a decrease in CAPS-5 scores and was equally effective in patients with common comorbidities that can make PTSD harder to treat. A greater percentage of patients receiving MDMA responded to treatment, no longer qualified for PTSD diagnosis, or entered remission, compared to patients receiving a placebo (Figure 2.) (Mitchell, 2021). At a long-term follow-up, 17 to 74 months after MDMA therapy administration, patient’s CAPS-5 scores had not significantly changed since treatment, indicating that MDMA provides long lasting PTSD symptom reduction. Patients expressed that they felt MDMA therapy was beneficial and experienced no adverse effects associated with drug abuse potential and suicidality. Patients also reported no decrease in cognitive functioning following MDMA treatment (Mithoefer, 2013).

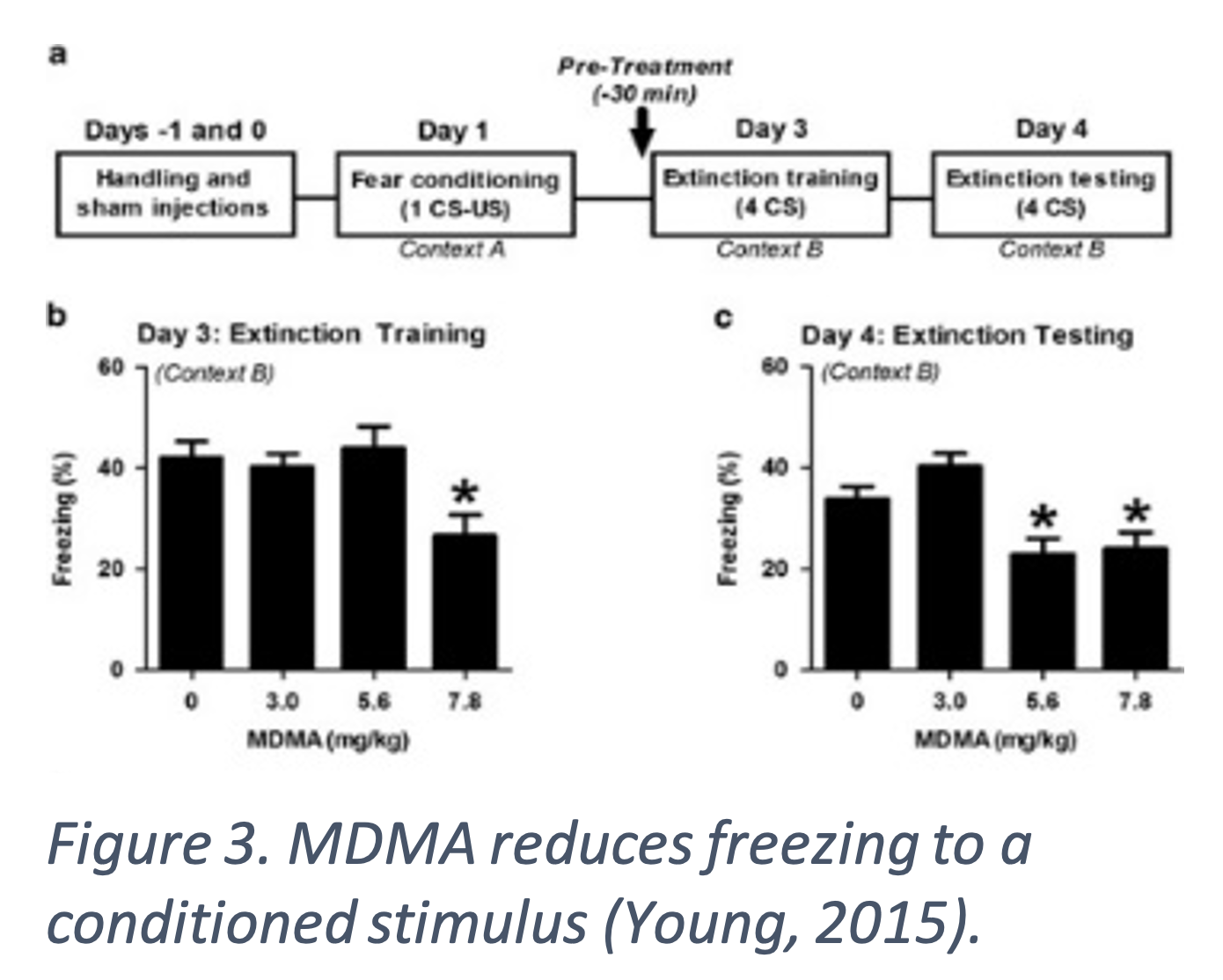

MDMA increases fear extinction indicated by reduced freezing in response to conditioned stimuli in mice. MDMA was administered before fear extinction training and mice given the highest doses had reduced freezing (Figure 3. b-c) (Young, 2015). Fear training was completed by pairing a sound with foot shocks. Fear extinction was tested by playing the sound without foot shocks and measuring how much the mice froze. Freezing indicates the mice remember the stimulus pairing and mimics PTSD symptoms. Fear extinction is a common part of exposure-based therapy for PTSD as it affects learning and memory associated with the triggering event (Young, 2015), (Young 2017). BDNF facilitates fear learning and extinction and those with reduced BDNF are less responsive to extinction therapy. MDMA increases expression of Fos, an early response gene, in the amygdala and mPFC and BDNF in the amygdala after extinction training in mice (Figure 4.). Both Fos and BDNF are markers of neuronal activity. The increase in fear extinction was eliminated when BDNF was inhibited, suggesting MDMA affects fear learning through a BDNF mechanism (Young, 2015). A serotonin transporter inhibitor blocked MDMA’s effect and inhibition of dopamine and norepinephrine transporters had no effect, indicating MDMA is working though serotonin pathways (Young 2017).

MDMA shows more safety and efficacy compared to the standard PTSD SSRI medications, paroxetine and sertraline. MDMA begins reducing symptoms 3-5 days after the first dose, whereas SSRIs require daily administration for at least two weeks to see results. MDMA is well tolerated, as fewer patients drop out of MDMA trials compared to paroxetine and sertraline trials, 6.85% versus 11.7% and 28%, respectively. MDMA has less long-term adverse reactions compared to SSRIs, although MDMA can cause some minor short-term adverse reactions. MDMA is only taken in sessions with a trained professional in a controlled environment, so there is less risk of overdose, withdrawal symptoms, or noncompliance (Feduccia, 2019). Overall, MDMA appears to be safe and effective for treating PTSD, perhaps more so than the current approved medications and therapies.

Other Drugs for Future Study

Psilocybin

Psilocybin has been studied to treat depression, anxiety, and alcohol addiction (Vollenweider, 2010), (Krediet, 2020). It helps with emotional processing by promoting fear extinction, neural plasticity, and reducing amygdala activity, often heightened with PTSD (Catlow, 2013), (Kraehenmann, 2015). Psilocybin also increases feelings of mindfulness, insight, openness, acceptance, and connectedness. A potential downside is that psilocybin can cause symptoms of heightened anxiety and confusion (Krediet, 2020).

Cannabinoids

Cannabinoids are drugs that act on the endocannabinoid system and are often derived from the cannabis plant. There are over 100 cannabinoids compounds, both natural and synthetic, ∆9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) are the most studied (Hill, 2018), (Freeman, 2019). Cannabinoids are used for other conditions like anxiety and pain, and medical cannabis has been legalized in 37 states (NCSL, 2022). The endocannabinoid system plays a large role in emotional memories and stress response. THC and CBD increase fear extinction and impact fear memory reconsolidation. THC can decrease amygdala reaction in response to triggering stimuli (Hill, 2018), (Krediet, 2020). There have been a few studies with small sample sizes with promising results that cannabinoids may be effective for treating PTSD (Roitman, 2014), (Jetly, 2015), (Hill, 2018). A potential downside is that cannabis use can increase risk for psychotic disorders for those already at high-risk, and it may cause cognitive impairments with frequent use, especially in adolescents (Krediet, 2020).

While neither psilocybin nor cannabinoids have been extensively studied to treat PTSD, they seem like potential candidates for treatment with more research. Meanwhile, ketamine and MDMA seem to be safe and effective treatments for PTSD. Overall, psychedelic drugs, often alongside psychotherapy, show promising results for treating PTSD symptoms compared to the current treatment recommendations of SSRIs and psychotherapy.

[+] References

Albott, C. S., Lim, K. O., Forbes, M. K., Erbes, C., Tye, S. J., Grabowski, J. G., Thuras, P., Batres-Y-Carr, T. M., Wels, J., & Shiroma, P. R. (2018). Efficacy, Safety, and Durability of Repeated Ketamine Infusions for Comorbid Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Treatment-Resistant Depression. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 79(3), 17m11634. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.17m11634. PMID: 29727073.

American Psychological Association. (2017). Medications for PTSD. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/ptsd-guideline/treatments/medications.

Catlow, B. J., Song, S., Paredes, D. A., Kirstein, C. L., & Sanchez-Ramos, J. (2013). Effects of psilocybin on hippocampal neurogenesis and extinction of trace fear conditioning. Experimental brain research, 228(4), 481–491. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-013-3579-0. PMID: 23727882.

Feder, A., Parides, M. K., Murrough, J. W., Perez, A. M., Morgan, J. E., Saxena, S., Kirkwood, K., Aan Het Rot, M., Lapidus, K. A., Wan, L. B., Iosifescu, D., & Charney, D. S. (2014). Efficacy of intravenous ketamine for treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA psychiatry, 71(6), 681–688. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.62. PMID: 24740528.

Feder, A., Costi, S., Rutter, S. B., Collins, A. B., Govindarajulu, U., Jha, M. K., Horn, S. R., Kautz, M., Corniquel, M., Collins, K. A., Bevilacqua, L., Glasgow, A. M., Brallier, J., Pietrzak, R. H., Murrough, J. W., & Charney, D. S. (2021). A Randomized Controlled Trial of Repeated Ketamine Administration for Chronic Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. The American journal of psychiatry, 178(2), 193–202. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20050596. PMID: 33397139.

Feduccia, A. A., Jerome, L., Yazar-Klosinski, B., Emerson, A., Mithoefer, M. C., & Doblin, R. (2019). Breakthrough for Trauma Treatment: Safety and Efficacy of MDMA-Assisted Psychotherapy Compared to Paroxetine and Sertraline. Frontiers in psychiatry, 10, 650. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00650. PMID: 31572236.

Freeman, T. P., Hindocha, C., Green, S. F., & Bloomfield, M. (2019). Medicinal use of cannabis based products and cannabinoids. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 365, l1141. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l1141. PMID: 30948383.

Hill, M. N., Campolongo, P., Yehuda, R., & Patel, S. (2018). Integrating Endocannabinoid Signaling and Cannabinoids into the Biology and Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 43(1), 80–102. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2017.162. PMID: 28745306.

Jetly, R., Heber, A., Fraser, G., & Boisvert, D. (2015). The efficacy of nabilone, a synthetic cannabinoid, in the treatment of PTSD-associated nightmares: A preliminary randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled cross-over design study. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 51, 585–588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.11.002. PMID: 25467221.

Kraehenmann, R., Preller, K. H., Scheidegger, M., Pokorny, T., Bosch, O. G., Seifritz, E., & Vollenweider, F. X. (2015). Psilocybin-Induced Decrease in Amygdala Reactivity Correlates with Enhanced Positive Mood in Healthy Volunteers. Biological psychiatry, 78(8), 572–581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.04.010. PMID: 24882567.

Krediet, E., Bostoen, T., Breeksema, J., van Schagen, A., Passie, T., & Vermetten, E. (2020). Reviewing the Potential of Psychedelics for the Treatment of PTSD. The international journal of neuropsychopharmacology, 23(6), 385–400. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijnp/pyaa018.

Miao, X. R., Chen, Q. B., Wei, K., Tao, K. M., & Lu, Z. J. (2018). Posttraumatic stress disorder: from diagnosis to prevention. Military Medical Research, 5(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40779-018-0179-0. PMID: 30261912.

Mitchell, J. M., Bogenschutz, M., Lilienstein, A., Harrison, C., Kleiman, S., Parker-Guilbert, K., Ot'alora G, M., Garas, W., Paleos, C., Gorman, I., Nicholas, C., Mithoefer, M., Carlin, S., Poulter, B., Mithoefer, A., Quevedo, S., Wells, G., Klaire, S. S., van der Kolk, B., Tzarfaty, K., … Doblin, R. (2021). MDMA-assisted therapy for severe PTSD: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Nature medicine, 27(6), 1025–1033. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01336-3. PMID: 33972795.

Mithoefer, M. C., Wagner, M. T., Mithoefer, A. T., Jerome, L., Martin, S. F., Yazar-Klosinski, B., Michel, Y., Brewerton, T. D., & Doblin, R. (2013). Durability of improvement in post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms and absence of harmful effects or drug dependency after 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine-assisted psychotherapy: a prospective long-term follow-up study. Journal of psychopharmacology (Oxford, England), 27(1), 28–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881112456611. PMID: 23172889.

National Institute of Mental Health. (2019, May). Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/post-traumatic-stress-disorder-ptsd.

NCSL. (2022, February 3). State Medical Cannabis Laws. National Conference of State Legislators (NCSL). Retrieved from https://www.ncsl.org/research/health/state-medical-marijuana-laws.aspx.

Passos, I. C., Vasconcelos-Moreno, M. P., Costa, L. G., Kunz, M., Brietzke, E., Quevedo, J., Salum, G., Magalhães, P. V., Kapczinski, F., & Kauer-Sant'Anna, M. (2015). Inflammatory markers in post-traumatic stress disorder: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. The lancet. Psychiatry, 2(11), 1002–1012. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00309-0. PMID: 26544749.

Quirk, M. C., Sosulski, D. L., Feierstein, C. E., Uchida, N., & Mainen, Z. F. (2009). A defined network of fast-spiking interneurons in orbitofrontal cortex: responses to behavioral contingencies and ketamine administration. Frontiers in systems neuroscience, 3, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/neuro.06.013.2009. PMID: 20057934.

Roitman, P., Mechoulam, R., Cooper-Kazaz, R., & Shalev, A. (2014). Preliminary, open-label, pilot study of add-on oral Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol in chronic post-traumatic stress disorder. Clinical drug investigation, 34(8), 587–591. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40261-014-0212-3. PMID: 24935052.

Schrader, C., & Ross, A. (2021). A Review of PTSD and Current Treatment Strategies. Missouri medicine, 118(6), 546–551. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8672952/. PMID: 34924624.

Sessa, B., Higbed, L., & Nutt, D. (2019). A Review of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)-Assisted Psychotherapy. Frontiers in psychiatry, 10, 138. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00138. PMID: 30949077.

USC Environmental Health & Safety. (n.d.). Overview of Controlled Substances and Precursor Chemicals. University of Southern California. Retrieved from https://ehs.usc.edu/research/cspc/chemicals/

Vollenweider, F. X., & Kometer, M. (2010). The neurobiology of psychedelic drugs: implications for the treatment of mood disorders. Nature reviews. Neuroscience, 11(9), 642–651. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2884. PMID: 20717121.

Watkins, L. E., Sprang, K. R., & Rothbaum, B. O. (2018). Treating PTSD: A Review of Evidence-Based Psychotherapy Interventions. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience, 12, 258. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00258. PMID: 30450043.

Young, M. B., Andero, R., Ressler, K. J., & Howell, L. L. (2015). 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine facilitates fear extinction learning. Translational psychiatry, 5(9), e634. https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2015.138. PMID: 26371762.

Young, M. B., Norrholm, S. D., Khoury, L. M., Jovanovic, T., Rauch, S., Reiff, C. M., Dunlop, B. W., Rothbaum, B. O., & Howell, L. L. (2017). Inhibition of serotonin transporters disrupts the enhancement of fear memory extinction by 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA). Psychopharmacology, 234(19), 2883–2895. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-017-4684-8. PMID: 28741031.

[+] Other Work By Teyline McLean

Meditation Helps Reduce Anxiety

Neuroanatomy

A study shows that mindfulness meditation can improve symptoms in Generalized Anxiety Disorder.

Brain Cells Die So You Can See

Neurophysiology

This study shows that a specific type of brain cells die during vision development so people can have properly functioning binocular vision.