Functional prions are in the central nervous system; how they influence memory!

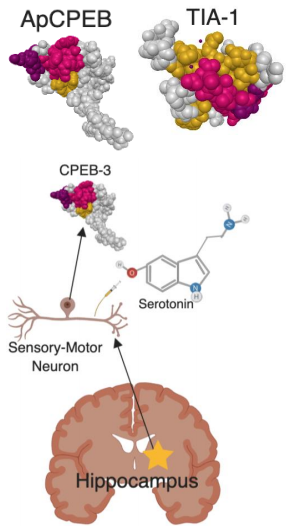

Prions are an incredible class of proteins which offer many beneficiary functions to the central nervous system, such as cytoplasmic polyadenylation element-binding protein (CPEB), its role in long-term memory and synaptic plasticity. Prions also serve as a harmful misfolded protein within the nervous system, this caused all prions to classically be identified as the forefront for neurodegenerative illnesses. TIA-1 is also a crucial functioning prion and it’s known for its role during stress in the brain and programed cell death. It is now known to be a key member of normal cell biology.

Author: Victor Cosovan

Download: [ PDF ]

Neuroanatomy

Prions are a new class of proteins; they are a proteinaceous infectious particle which lacks nucleic acids but alter protein structure upon contact with specific neurological structures. Originally prions were found to be etiological agents of neurodegenerative diseases such as, Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, kuru, and transmissible encephalopathies. The study of specific functional prions is important in understanding how synapses are formed and how the mechanisms function. By understanding the role of CPEB in synaptic function, many medicines for neurodegenerative diseases and other synaptic affiliated disorders can be restored or vindicated for the patients. TIA-1 is a wonderful example of a prion structure in which it facilitates normal cellular function in the duration of the cell’s life span, but TIA-1 also has situations when it activates mechanisms which may lead to pathological and physiological irregularities leading to many forms of neurological disease.

A great representation of a prion is most formally known as its acronym form, CPEB (cytoplasmic polyadenylation element-binding protein). Recently, a hypothesis has emerged that prion like, self-templating mechanisms also underlie a variety of neurodegenerative disorders such as, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, and Huntington’s disease. New found evidence suggests that a variety of neurodegenerative conditions that are not transmissible between individuals as prions traditionally may nevertheless be caused by self-templating, prion-like mechanisms such as CPEB and TIA-1 or other prion like proteins. In this experiment a marine sea snail was stimulated for a siphon reflex and under vivo and vitro, the learning of the 5-HT marked synapses were observed for 72 hours for a change in gene expression in the synapse and for presence of CPEB and its role in the two types of memory construction. It is still needed to be researched about how that prion-like proteins can contribute to normal physiological processes in the nervous system, for only a few cases have been identified and studied. Prions pose a crucial role in neurophysiology and are needed for synaptic regulation.

THE ROLE OF CPEB IN APLYSIA

This prion like structure is known and named for its characteristic of binding multiple adenosine bases which causes a change in the protein shape, thus function too. For this study, the CPEB is tested within the cytoplasm of a sensory-motor neuron in a marine sea snail, Aplysia californica due to the simplicity of its nervous system. CPEB was examined for how conversion from a soluble to a prion-like conformation regulates protein synthesis at the synapse, thus modulating both the maintenance of synaptic plasticity and long-term memory. Aplysia is the subject because it has a number of simple reflexes that can be modified by different forms of learning. One of the tested examples includes the gill-withdrawal reflex when the siphon of the snail is rapidly withdrawn due to stimuli. The neural circuit of the snail’s reflex has an important monosynaptic connection in were sensory neurons that innervate the siphon make direct connections with the motor neurons, thus moving the gill in the reflex mechanism. As behavioral memory works, there are two forms of memory, short-term (a few minutes) to long-term memory (days or weeks) with in the synaptic plasticity of the sensory and motor neurons. The short-term memory form depends on modifications of preexisting proteins mediated in part by protein kinase A which will strengthen the preexisting connections. Also, for the long-term form of memory, it is required that both new protein synthesis and CREB-mediated gene expression, which drives the remodeling of current existing synapses and to form new synaptic connections. In the role of synaptic plasticity, gene products are sent to all synapses for the mechanism of long-term memory synapse in each neuron because of the release of 5-HT (serotonin) is a marker of the synapses which will receive these gene products. The pathway for synapse specific long-term memory is a bidirectional process between the synapse and the nucleus. The synaptic marker for stabilization in the neuron was found to be activation of transitionally dominant mRNAs. CPEB was found to be the activator of dominant mRNAs in the process of elongation of the poly-A tail. Polyadenylation-dependent translational control requires a cis-acting cytoplasmic polyadenylation element (CPE) in the 3′ UTR of the mRNA were CPEB can bind and recruit a variety of partner proteins to further an action. It was found that ApCPEB can be activated at the terminal by just a single pulse of 5-HT (Figure 1). The aggregated conformation that is the active form of CPEB promotes translation of target mRNAs, it is not harmful to the cell, usually prions in their aggregated state can bare harm. Using green florescent protein, they were able to tag CPEB and follow it through its aggregated state and use the florescent dye to image cells upon stimulation. The results show that the two forms of CPEB work in sequence and play a role in synaptic consolidation.

Another study focused on detecting aggregated ApCPEB by adding a florescent marker on them. After 5-HT pulses on the sensory-motor neuron on Aplysia, it was found that more aggregated ApCPEB were found in the synapses. It was predicted that blocking aggregated ApCPEB would then destabilize the maintenance of long-term facilitation of the synapses, but actually after injecting the blocking anti-body, synaptic facilitation did not persist beyond 48 hours after Ab464- injected cells. Thus, it is supported that the multimeric form of ApCPEB is involved in long-term stabilization of synaptic activity. Learning-induced activation of ApCPEB initiates a cellular positive feedback loop within the synapses, whereas ApCPEB promotes the activation of more ApCPEB through specific conformational changes within the synapse. Thus, this is potentially a powerful mechanism for generating a self-perpetuating local signaling at the synapse.

A study in the CPEB in the Drosophila brain suggests that the expresser epigenetic prion like protein, Orb2/ CPEB are acting to stabilize activity-dependent changes within the synapse. Prion like conversion of Orb2 is necessary for long-term memory because failure to form Orb2 amyloid leads to the loss of facilitation in sensory-motor neuron synapses on inhibition of the ApCPEB oligomers. The break in the mechanism for ApCPEB is a leading factor in failure to sustain or form consolidated memories due to the lack of synaptic regulation. Flies with Orb2 deletion fail to show characteristics of long-term memory tasks and functions.

CPEB IN THE MAMMALIAN BRAIN

In recent studies, they searched for CPEB orthologs in the mouse brain and identified four isoforms of CPEB, CPEB-1 to CPEB-4. Of these four isoforms, CPEB-3 resembles ApCPEB because it is neuronally specific translational regulator with an unstructured Q/N-rich domain at its N-terminus and RNA-binding domains at its C-terminus. This resembles the make-up of prion like structures. The studies in hippocampal neurons provide evidence that mCPEB-3, like its invertebrate orthologs, ApCPEB and Orb2, displays the basic features of prion proteins within the nervous system (Figure 1). It was found that CPEB-3 binds to and also represses the translation of target mRNAs as a regulatory in long-term facilitation. When CPEB-3 is activated by specific post-translational modifications during active learning, CPEB-3 was able to transition from a soluble protein into an aggregated form, which thus promotes the translation of the AMPA receptor. This process leads to maintenance of synaptic activity in the synapse. In order to determine the role of CPEB-3 in synaptic plasticity and memory, a conditional knockout strain of CPEB-3 was generated and tested. It was revealed that CPEB-3-mediated protein synthesis is crucial for the maintenance of protein synthesis dependent long-term potentiation (LTP), but as found, not for short-term LTP or memory acquisition due to a different mechanism of synaptic regulation. Furthermore, CPEB-3 has shown that loss of the N-terminus, which is necessary for its aggregated form, loses its ability to maintain long-term synaptic plasticity and memory. In this process it can be concluded that AMPA receptor subunits, GluA1 and GluA2 provide the first evidence for a prion-like mechanism to sustain memory in the mouse brain, during both the processes of consolidation and maintenance.

PRIONS LEAD TO PATHOLOGICAL ILLNESS AND MAJOR NONTRANSMITTABLE DISEASE

Unlike pathological prions, aggregated prions within the nervous system are regulated physiologically and post no current threat as traditionally thought to be. CPEB expression is regulated by microRNAs (miRNAs). Therefore, a neuron-specific miRNA, like miRNA-22 inhibits ApCPEB mRNA through many 3′ UTR binding sites and it is downregulated by serotonin by increasing and even enhancing long-term memories. Whereas, over expression will inhibit longterm facilitation of the synapse and block the formation or consolidation of new memories. The prion, ApCPEB has coiled-coil α-helices that can mediate prion-like oligomerization, unlike βsheets, coiled-coils are responsive to cellular and environmental signals, therefore the prion can be regulated. This is what sets functional prions apart from pathologically harmful prions.

The pathogenic proteins associated with Alzheimer’s disease, Huntington’s disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis are each non-transmittable disorder, for example amyloid β, in Alzheimer’s disease and huntingtin, in Huntington’s disease follow a spontaneous switch from a regular conformation to a self-propagating, aggregated structure that is cytotoxic. In greater detail, yeast prions are characterized by their ability to pass on phenotypes from mother to daughter cell in a stable, non-Mendelian manner and also without involvement of nucleic acid–based mechanisms within the cells.

ADDITIONAL FUNCTIONAL PRIONS IN THE BRAIN

There are not just the basic prions in regulating synaptic function, there are other remarks about prions in the central nervous system. TIA-1for example, was identified as a functional prion-like protein in the mouse hippocampus. TIA-1 can facilitate the assembly of cytoplasmic aggregates known as stress granules in response to extreme environmental condition, or when the cell is under ‘stress.’ This functionality is what allows the prion to be a key member in programed cell death. Like the previous prions discussed, TIA-1 aggregates are amyloid-rich and show heritability in a yeast assay. TIA-1 is important in regulatory function which prevents neurodegenerative changes in the brain.

[+] References

Rayman, J. B., & Kandel, E. R. (2017). Functional prions in the brain. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology, 9(1), a023671. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5204323/

Si, K., & Kandel, E. R. (2016). The role of functional prion-like proteins in the persistence of memory. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology, 8(4), a021774.

Casadio, A., Martin, K. C., Giustetto, M., Zhu, H., Chen, M., Bartsch, D., ... & Kandel, E. R. (1999). A transient, neuron-wide form of CREB-mediated long-term facilitation can be stabilized at specific synapses by local protein synthesis. Cell, 99(2), 221-237

Fioriti, L., Myers, C., Huang, Y. Y., Li, X., Stephan, J. S., Trifilieff, P., ... & Kandel, E. R. (2015). The persistence of hippocampal-based memory requires protein synthesis mediated by the prion-like protein CPEB3. Neuron, 86(6), 1433-1448

Fiumara, F., Fioriti, L., Kandel, E. R., & Hendrickson, W. A. (2010). Essential role of coiled coils for aggregation and activity of Q/N-rich prions and PolyQ proteins. Cell, 143(7), 1121-1135

Fiumara, F., Rajasethupathy, P., Antonov, I., Kosmidis, S., Sossin, W. S., & Kandel, E. R. (2015). MicroRNA-22 gates long-term heterosynaptic plasticity in Aplysia through presynaptic regulation of CPEB and downstream targets. Cell reports, 11(12), 1866-1875

Frey, U., & Morris, R. G. (1997). Synaptic tagging and long-term potentiation. Nature, 385(6616), 533-536

Gebauer, F., & Richter, J. D. (1996). Mouse cytoplasmic polyadenylylation element binding protein: an evolutionarily conserved protein that interacts with the cytoplasmic polyadenylylation elements of c-mos mRNA. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 93(25), 14602-14607

Gilks, N., Kedersha, N., Ayodele, M., Shen, L., Stoecklin, G., Dember, L. M., & Anderson, P. (2004). Stress granule assembly is mediated by prion-like aggregation of TIA-1. Molecular biology of the cell, 15(12), 5383-5398

Hake, L. E., & Richter, J. D. (1994). CPEB is a specificity factor that mediates cytoplasmic polyadenylation during Xenopus oocyte maturation. Cell, 79(4), 617-627

Hou, F., Sun, L., Zheng, H., Skaug, B., Jiang, Q. X., & Chen, Z. J. (2011). MAVS forms functional prion-like aggregates to activate and propagate antiviral innate immune response. Cell, 146(3), 448-461

Huang, Y. S., Kan, M. C., Lin, C. L., & Richter, J. D. (2006). CPEB3 and CPEB4 in neurons: analysis of RNA‐ binding specificity and translational control of AMPA receptor GluR2 mRNA. The EMBO journal, 25(20), 4865- 4876

Keleman, K., Krüttner, S., Alenius, M., & Dickson, B. J. (2007). Function of the Drosophila CPEB protein Orb2 in long-term courtship memory. Nature neuroscience, 10(12), 1587

Krüttner, S., Stepien, B., Noordermeer, J. N., Mommaas, M. A., Mechtler, K., Dickson, B. J., & Keleman, K. (2012). Drosophila CPEB Orb2A mediates memory independent of Its RNA-binding domain. Neuron, 76(2), 383-395

Martin, K. C., Casadio, A., Zhu, H., Yaping, E., Rose, J. C., Chen, M., ... & Kandel, E. R. (1997). Synapse-specific, long-term facilitation of aplysia sensory to motor synapses: a function for local protein synthesis in memory storage. Cell, 91(7), 927-938

Morgan, M., Iaconcig, A., & Muro, A. F. (2010). CPEB2, CPEB3 and CPEB4 are coordinately regulated by miRNAs recognizing conserved binding sites in paralog positions of their 3′-UTRs. Nucleic acids research, 38(21), 7698-7710.

[+] Other Work By Victor Cosovan

Gene mutation heals traumatic brain injury

Neurophysiology

Traumatic brain injuries heal differently for different people. That is because of an apoptotic gene, P53 which is mutated in some people and leads to higher resilience of programmed cell death. Thus, there is increased recovery in severe TBI patients with the mutated P53 gene.

Structural and functional prion malfunction as a catalyst for Alzheimer’s disease

Neuroscience In Review