Live to Smell Again: SARS-CoV-2 Induced Anosmia and Regeneration of Olfactory Neurons and Epithelium.

This article examines research done to deduce the regenerative capability of olfactory cells in the inner lining of the nose after contracting COVID-19. Using Syrian golden hamsters as test subjects, the study carefully measures the layer of cells after COVID-19-induced cell deaths and the related phenomena in loss of the ability to smell odors (Urata et al. 2021).

Author: Kelly Stewart

Download: [ PDF ]

Neurophysiology

Background

Viral takeover of olfactory epithelial cells can infect the brain with COVID-19(Yachou et. al 2020). The destruction of these cells in the nasal passage is the first line of defense observed in the Syrian golden hamsters in Urata et al.’s experiment. Over a period of three to four weeks after being infected with COVID-19, olfactory cells were regrown, and sense of smell returned to nearly normal levels. This experiment is valuable insight into the process used by the nasal passage to protect the brain from COVID-19, and the possibility of these findings holding true for humans is optimistic for patient outcomes after a COVID-19 infection (Urata et al. 2021). Anosmia is becoming a consistent and identifiable diagnostic symptom for patients with COVID-19 (Hornuss et al. 2020).

Anosmia diagnosesis often split into sinus-related or non-sinus related causes (Fonteyn et al. 2014). Most commonly, damage to olfaction is due to infection from colds and flus, especially when olfactory dysfunction occurs for long periods of time after an infection (de Haro-Licer et al. 2013). Unlike other sensory systems, olfaction does not require moving to the brain through the spinal cord: olfactory sensory neurons connect with the olfactory bulb in the brain by passing through openings at the top of the nasal passage (Morris & Schaeffer 1953). The sense of smell is connected to the amygdala (Zald & Pardo 1997). Losing the sense of smell carries with it a wide range of problems that affect quality of life: loss of appetite, weight loss, malnutrition, inability to sense hazardous chemicals by smell, decreased food taste sensations and potential memory impairments connected to smell (Glezer et al. 2020). Regenerating cells in the nasal passage may offer the chance to regain the ability to smell odors and improve quality of life for survivors of COVID-19 (Urata et al. 2021).

Methods

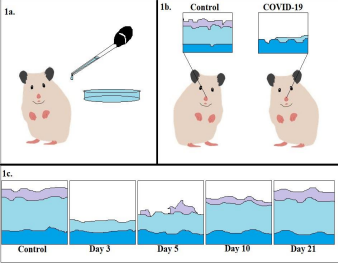

In Urata et al.’s experiment, Syrian golden hamsters were exposed to SARS-CoV-2 with a nasal inoculation in different amounts: 50-100μL. Body temperatures and weights were recorded throughout the experiment, and by the end, animals were humanely euthanized. Samples of tissue from their nasal passages and olfactory bulbs were harvested from the heads of the hamsters and fixed with stain to mark the presence of SARS-CoV-2-infected cells(Urata et al. 2021).

Results

Over the course of the experiment, none of the subjects died from the virus, but all experienced anosmia and weight loss. Measurements of the thickness of the nasal epithelium were indications of how severe the body’s response to the virus was: by day three after being infected, a near total destruction of olfactory neuron cells lining the nasal passages was observed. Viral load was measured in nasal and lung mucus over time. The clearing of viral load in the mucosal secretions was a positive indication of healing taking place in the nasal passages: by days 5-10, the virus was barely detected. By day 21, the regeneration process of olfactory receptor neurons and epithelial cells was complete, and function was restored. Only a slight difference in thickness between control animals that were not infected and recovering animals was observed (Urata et al. 2021).

Discussion

The loss of olfaction and gustation are common symptoms reported by those with COVID-19 (Parma et al. 2020). Anosmia is hypothesized to be connected to increased survival rates in COVID-19 infections and is independent of the severity of the infection (Hopkins et al. 2021). Onset of anosmia may be connected to outcomes of the disease, as the virus can enter the central nervous system by making use of nasal epithelial and supporting cells (Urata et al. 2021). Inflammation-guided apoptosis of infected or damaged cells may account for the anosmia experienced by those who fail to regain any improvement in olfaction (Mastrangelo et. al 2021). Loss of an entire sense can be and is traumatic to endure, and while the exact mechanism of anosmia in COVID-19 patients is not currently known for certain, small studies with animals and people may help reduce the long-term impact the pandemic has on patients and help create new treatments for those that suffer from chemosensory impairment.

[+] References

Urata, S., Maruyama, J., Kishimoto-Urata, M., Sattler, R. A., Cook, R., Lin, N., Yamasoba, T., Makishima, T., & Paessler, S. (2021). Regeneration Profiles of Olfactory Epithelium after SARS CoV-2 Infection in Golden Syrian Hamsters. ACS chemical neuroscience, 12(4), 589–595. https://doi.org/10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00649.

de Haro-Licer, J., Roura-Moreno, J., Vizitiu, A., González-Fernández, A., & González-Ares, J. A. (2013). Long term serious olfactory loss in colds and/or flu. Acta otorrinolaringologica espanola, 64(5), 331–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otorri.2013.04.003.

Fonteyn, S., Huart, C., Deggouj, N., Collet, S., Eloy, P., & Rombaux, P. (2014). Non-sinonasal related olfactory dysfunction: A cohort of 496 patients. European annals of otorhinolaryngology, head and neck diseases, 131(2), 87–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anorl.2013.03.006.

Morris, H; Schaeffer, JP (1953). Morris' Human Anatomy: A Complete Systematic Treatise (11 ed.). New York: Blakiston. pp. 1218–1219.

Yachou, Y., El Idrissi, A., Belapasov, V., & Ait Benali, S. (2020). Neuroinvasion, neurotropic, and neuroinflammatory events of SARS-CoV-2: understanding the neurological manifestations in COVID-19 patients. Neurological sciences : official journal of the Italian Neurological Society and of the Italian Society of Clinical Neurophysiology, 41(10), 2657–2669. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-020-04575-3.

Zald, D. H., & Pardo, J. V. (1997). Emotion, olfaction, and the human amygdala: amygdala activation during aversive olfactory stimulation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 94(8), 4119–4124. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.94.8.4119.

Glezer, I., Bruni-Cardoso, A., Schechtman, D., & Malnic, B. (2020). Viral infection and smell loss: The case of COVID-19. Journal of neurochemistry, 10.1111/jnc.15197. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnc.15197.

Hopkins, C., Lechien, J. R., & Saussez, S. (2021). More that ACE2? NRP1 may play a central role in the underlying pathophysiological mechanism of olfactory dysfunction in COVID-19 and its association with enhanced survival. Medical hypotheses, 146, 110406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2020.110406.

Mastrangelo, A., Bonato, M., & Cinque, P. (2021). Smell and taste disorders in COVID-19: From pathogenesis to clinical features and outcomes. Neuroscience letters, 748, 135694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2021.135694.

Hornuss, D., Lange, B., Schröter, N., Rieg, S., Kern, W. V., & Wagner, D. (2020). Anosmia in COVID-19 patients. Clinical microbiology and infection : the official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, 26(10), 1426–1427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2020.05.017.

Parma, V., Ohla, K., Veldhuizen, M. G., Niv, M. Y., Kelly, C. E., Bakke, A. J., Cooper, K. W., Bouysset, C., Pirastu, N., Dibattista, M., Kaur, R., Liuzza, M. T., Pepino, M. Y., Schöpf, V., Pereda Loth, V., Olsson, S. B., Gerkin, R. C., Rohlfs Domínguez, P., Albayay, J., Farruggia, M. C., … Hayes, J. E. (2020). More Than Smell-COVID-19 Is Associated With Severe Impairment of Smell, Taste, and Chemesthesis. Chemical senses, 45(7), 609–622. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/bjaa041.

[+] Other Work By Kelly Stewart

Empathy & Oxytocin: Prairie Voles

Neuroanatomy

This study examines the ability for prairie voles to feel empathy and consolation towards one another (Burket et al. 2016). As a socially complex animal, but cognitively less advanced than other mammals, it was not thought that rodents experienced empathy—this study researches the extent to which prairie voles feel empathy and express consolation behaviors to other, stressed, prairie voles.